|

By Tom Fournier

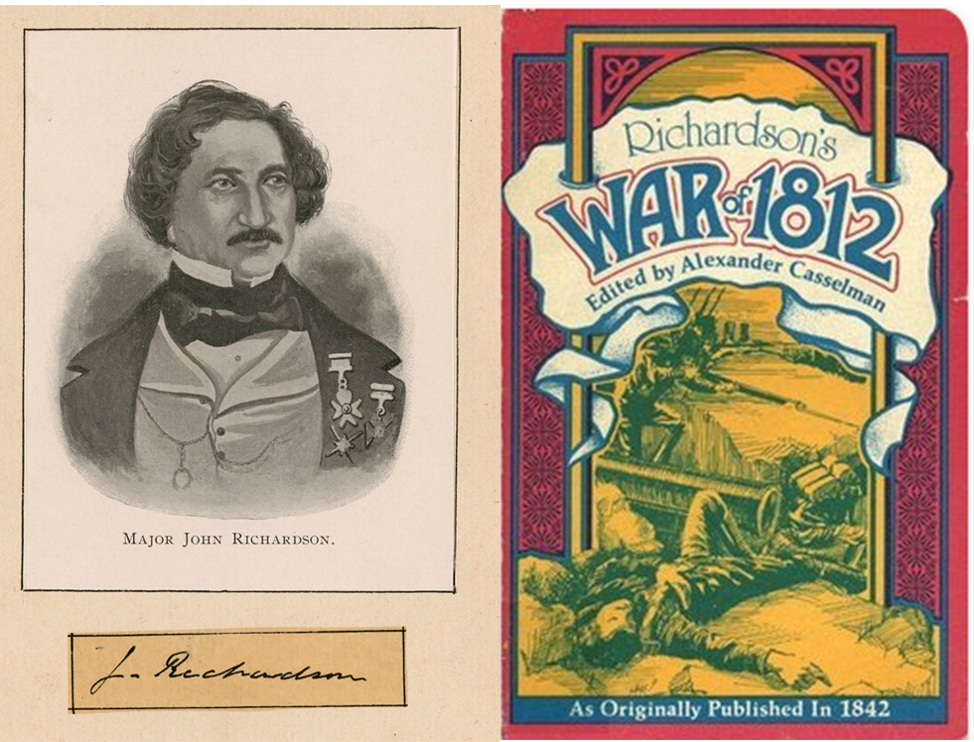

When I think of John Richardson, it is because of his time with the 41st Regiment of Foot during the War of 1812. He turned those experiences into a widely read and often cited book on the War of 1812. The most common form is Richardson’s War of 1812 edited by Alexander Casselman. Richardson was born in Upper Canada on 4 October 1796 in the Niagara region. His father Robert had come to Canada from Scotland as a surgeon with the Queen’s Rangers. His mother was Madelaine Askin daughter of Joseph Askin (the famous fur trader and merchant) and Manette an indigenous woman. Richardson spent his adolescent years in Amherstburg on the Detroit River. In July 1812, Richardson, at the age of 15, joined the 41st Regiment as a Gentleman Volunteer. A Gentleman Volunteer was an individual who wished to join the Officers of a regiment but for whom there was no place. The Gentleman Volunteer would serve in the ranks but mess with the Officers. They would hope to distinguish themselves in battle and earn a promotion to the rank of Officer. Richardson took part in a number of military engagements in the Lake Erie area (the Right Division for the British) including the Battle of the River Raisin. You can read more about Richardson in this previous blog post. For the Battle of the River Raisin, Richardson was a participant in the action, and he wrote about it as a historian but interestingly, he also wrote about it as a novelist in his book “The Canadian Brothers”. My thought is that it would be interesting to look at the novel for a far more descriptive and atmospheric account of the lead up to the battle without Richardson’s need to act as a historian or journalist (as he spent much of his life).

0 Comments

By Tom Fournier

When I think of John Richardson, it is because of his time with the 41st Regiment of Foot during the War of 1812. He turned those experiences into a widely read and often cited book on the War of 1812. The most common form is Richardson’s War of 1812 edited by Alexander Casselman. I have had the good fortune of seeing an original copy of the 1842 edition in the holdings of the Royal Welsh Museum. This was once the property of another member of the 41st Regiment who underscored passages and made margin notes critical of Richardson and many Officers of the 41st Regiment (perhaps a subject for another day). Richardson was very proud of his time with the 41st Regiment and he was extremely protective of its reputation. This can be seen in his passionate defense of the Officers of the 41st Regiment as a reaction to comments attributed to Major General Sir Isaac Brock in the book written by his nephew Ferdinand Brock Tupper. That defense can be read here. By Tom Fournier There was some recent excitement over photos of a coat that I saw in the old Welch Regiment Museum in Cardiff from a trip back in 2006. It is now in the holdings of the Regimental Museum of the Royal Welsh and the curator of the museum, Richard Davies was kind enough to pull out the coat and take some pictures. This is the coat of a Grenadier Officer of the 41st Regiment circa 1822. Unfortunately there is no record of who the coat belonged. This first two photos are of the coat in a display case from my original visit. The following pictures are those sent by Richard:

Click on the tweet below to be taken to Twitter to read the complete thread.

Periodically you may need to click on "show this thread" or "show replies" to unroll the entire 200+ tweet thread.

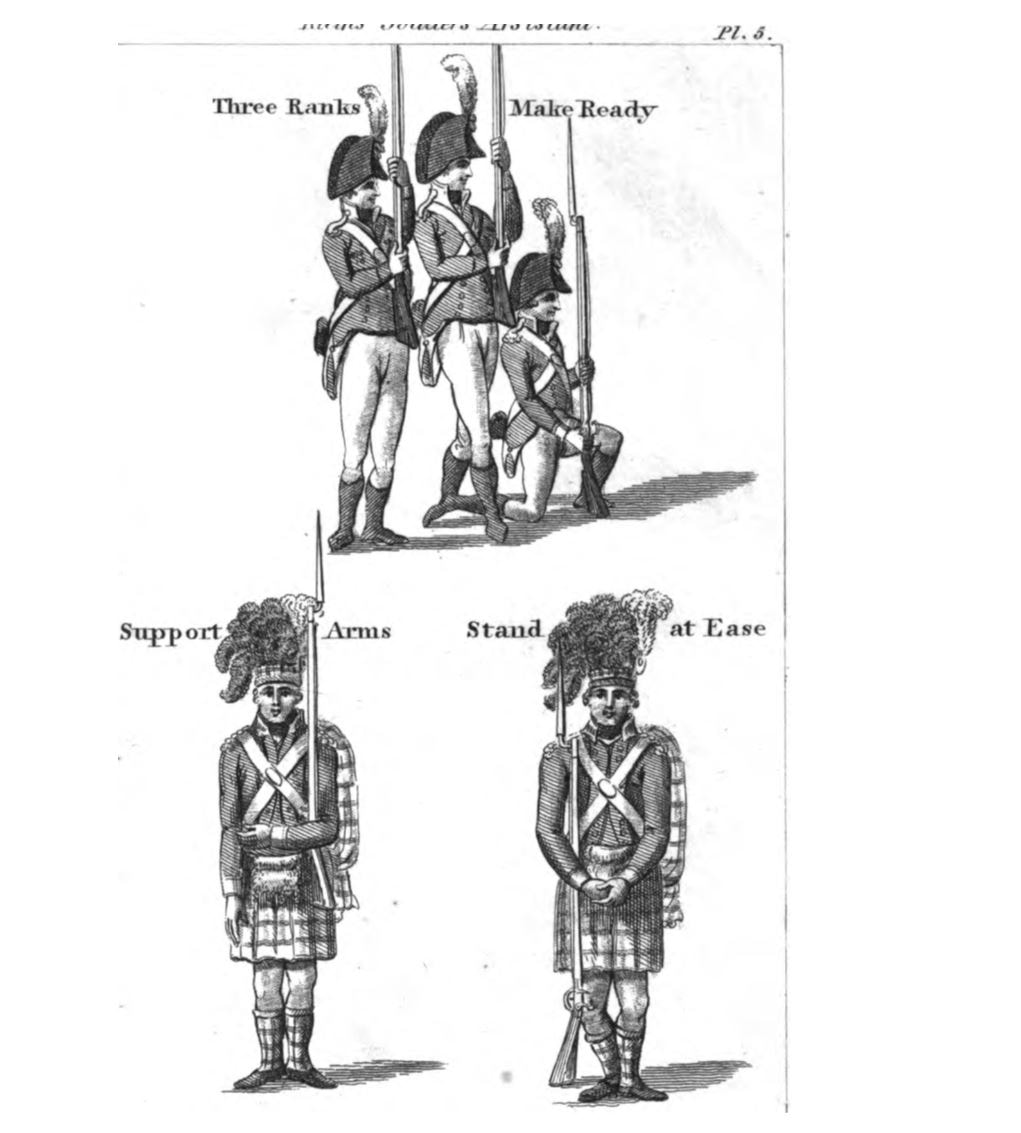

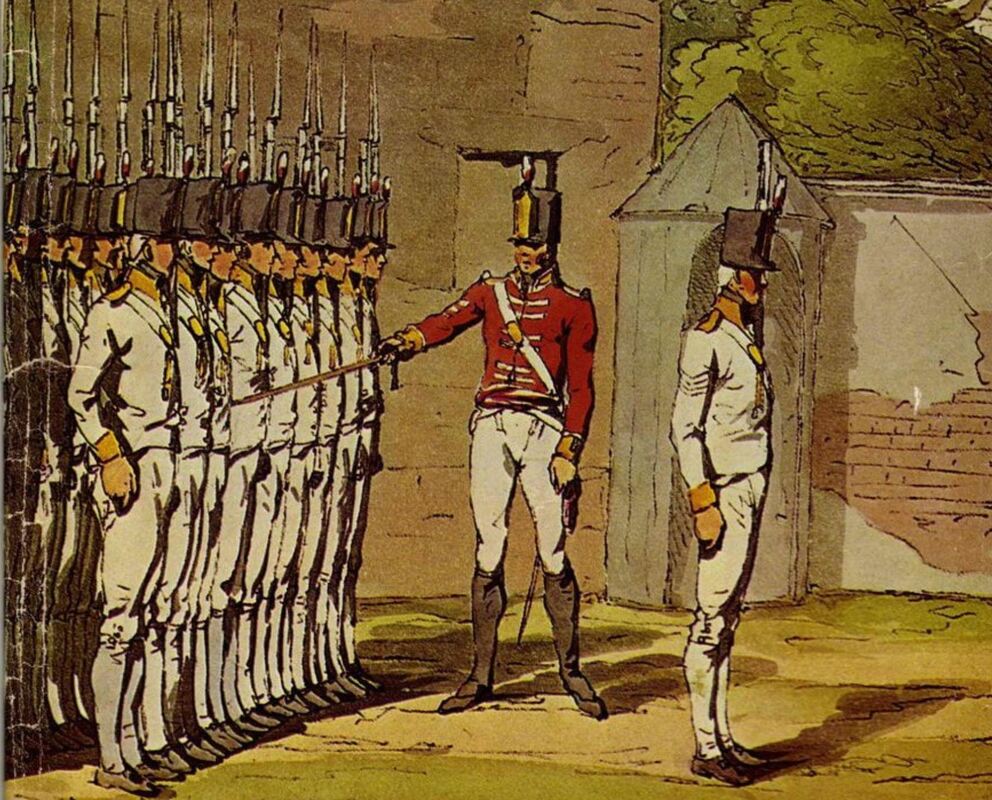

By Abel Land As promised, this is the next dispatch in the series, looking at how the serjeants would formulate the basic training of the recruit during the current war in America. Last week the content was on the foundation position for the recruit without arms; this week, the topic will be on how to stand at ease as explained in the Rules and Regulations 1807.

I would at this time like to backtrack a bit and thank one person who has helped me research and look critically at period manuals, along with clarification on some terms. This person puts his heart and soul into the knowledge of the late 18th and 19th-century foot drill — Ewan Wardle program development officer at Fort York National Historic Site in Toronto, Ontario. Thanks for your dedication to further our knowledge of historic military exercises. By Abel Land This is a new idea to help pass on the information acquired on foot drill of his Majesties forces during the North American conflict of 1812. Each Wednesday, there will be a new dispatch, including excerpts from the manuals employed to help train recruits.

This week's post is on the position of the soldier, not under arms. This starting post sets the foundation into which all foot drill is rooted. This first manual is the Rules and Regulations 1807, now the dates of for the conflict are 1812-15, why is a book published in 1807 crucial, the General Regulations and Orders from 1811, and 1815 both have this to say on the subject; “Every Serjeant of Cavalry and Infantry is required to have in his Possession a Copy of the Abstract of the Rules and Regulations for the Manual and Platoon Exercises; Formations, Field-Exercises, and Movements of His Majesty's Forces, which was printed for their Use, and issued, in the Month of January, 1807.” (Orders and Regulations 1811, 89) This manual should be the most common reference for all serjeants conducting foot drill, unless ordered differently, or future military historians in the 21st century where there will be multiple other sources to do research from. 1807 breaks the exercise down into three sections, the first is of the drill or instruction of the recruit, in 40 parts. The first section, which will be looked at over the next few posts, is on training without arms, beginning with the position of the soldier. By Tom Fournier

Whenever I hear the adage “if he did not have bad luck, he would have no luck at all”, I think of Porter Hanks. Lieutenant Porter Hanks is most often known as the American Officer who surrendered Fort Mackinac to an attacking British force representing one of the first land actions associated with the War of 1812. By Tom Fournier

My knowledge or interests do not naturally align with science or medicine but I could not resist this list of medical supplies that come from the Messages and Letters of William Henry Harrison; Volume 2 Part 2. Harrison was governor of the Indiana Territory and led the American military forces at the victories at Tippecanoe (1811) and Moraviantown (1813). He had command of Fort Meigs in Ohio in 1813. To my thinking, medical knowledge was at a strange crossroads at this time. Knowledge of anatomy had become quite advanced but the understanding of how it all worked still fell to a notion that the body had an ideal equilibrium and to solve for an illness or disruption meant restoring that equilibrium. Treatments such as bleeding, purging or blistering were still common. Equilibrium could be restored by releasing things like blood, urine, stool or perspiration. The body had four humours (blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile) and too much or too little of any of these humours would result in illness. |

AuthorsThese articles are written and compiled by members of the 41st Regiment Living History Group. Archives

January 2023

Categories |