Bored Officers, An Afternoon of Whisky and a Deserter on the Loose in Detroit. What Could Go Wrong?4/14/2019 By Tom Fournier

This incident has fascinated me for some time. It happened in 1805 in Detroit involving Officers of the British Army (41st Regiment) and the U.S. Army. By way of some background, Officers from the British and American armies stationed in remote outposts with limited society, were there to observe each other, but they would often end up taking advantage of their common background and experiences to develop friendships and a culture of visiting. The British had a policy of rounding up and returning American deserters to the U.S. Army. They asked for reciprocal actions or support from the Americans. For the Americans, this proved more difficult in or near American communities as their citizens were protective of British deserters seeking liberty and a new life in the United States.

0 Comments

By Tom Fournier

One of my favourite books is “This Was Montreal in 1814, 1815, 1816 & 1817” by Lawrence M. Wilson. It is simply a number of excerpts from the Montreal Herald that gives insights as to what life in Montreal might have been like during the Regency era. I particularly like the “society pages” type descriptions of the balls. Two of these I will share in this article. By Tom Fournier

March 11, 1719 represents the founding of the 41st/Welch Regiment, one of the key lineages in the current Royal Welsh. This blog looks at the evolutions, integrations and amalgamations as well as some key highlights along their history. On March 13, 1719 we have the founding of Colonel Edmund Fielding’s Regiment of Invalids. They formed from out pensioners from the Royal Hospital at Chelsea. This was the humble beginnings for the 41st Regiment of Foot (which would go on to become the Welch Regiment, then the Royal Welsh Regiment and ultimately the Royal Welsh).

By Tom Fournier

Oh, the gems you come across when doing research! I believe most of us realize that the average British soldier was not a choirboy. They were volunteers from the most poor and downtrodden. They may have volunteered to escape the prospects of a domestic situation that they did not like. They were also forced conscripts from the judicial system; rather than face transportation to a penal colony or other punishment, a life in the army was offered as an alternative. The Duke of Wellington was purported to say,” I don't know if they frighten the enemy, but they scare the hell out of me." By Tom Fournier

Some years ago, I had the good fortune to do some work at the National Archives (Public Records Office) in Kew (London) during a visit to the U.K. As I was going through the casualty returns for the 41st Regiment during their time in Canada, I noticed for some of the early years there were also included statements of debts for some of the individuals that died along with the corresponding credits (outstanding pay and the results of the sale of their personal necessaries). I thought it an interesting perspective to see what some of these individuals had as personal items. Interesting, yes. Fascinating insights, certainly. And unexpectedly, sad. Their life, all their worldly possessions summed up in a little chit, haphazardly stuck between the pages of a casualty return. Here are several of them: By Tom Fournier Scrolling through microforms you are never quite sure what might catch your eye. I came across a table detailing a return of regimental court martials for the time period of 22nd April to 1st October, 1812 for the 103rd Regiment of Foot.

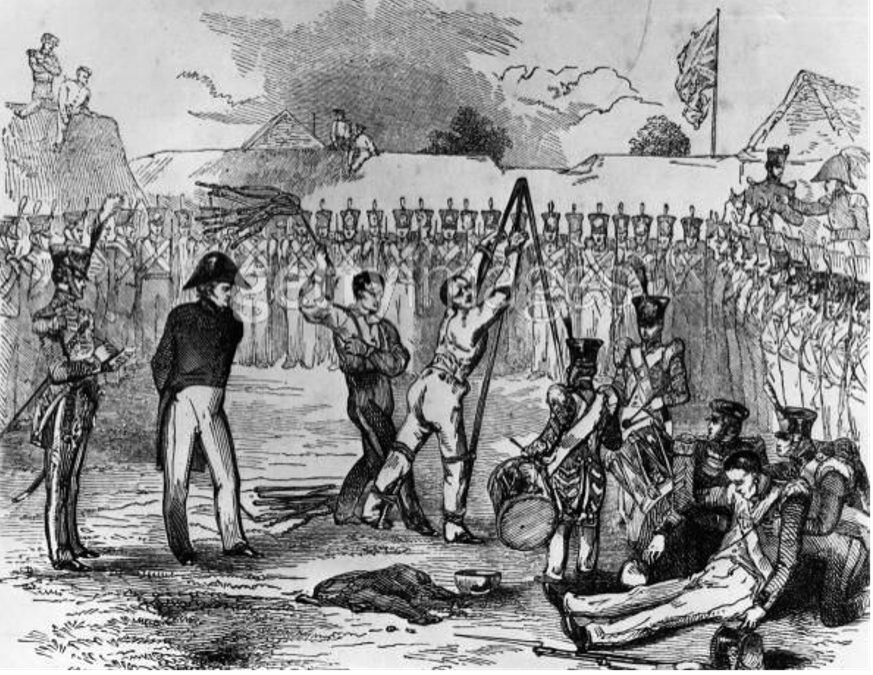

The 103rd Regiment was formed from the 9th Garrison Regiment in 1809 and arrived in Canada in 1812. Its character was that of being predominantly young recruits. The 103rd Regiment, largely due to its youthful and inexperienced character did not have an active war. By 1814 they were moved to Upper Canada. They are noted for having marched a lengthy distance to the sound of the guns (much of it at the double) to help shore up the British line at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane. They were next in action at the night assault on Fort Erie and were in the column that attacked along the water to the Douglas Battery. American guns loaded with canister decimated the column with the 103rd Regiment’s commanding officer, Hercules Scott[i] amongst the dead. For their service in these two actions, the 103rd Regiment earned the Battle Honour “Niagara”. The table of court martials gives us an opportunity to learn more about discipline in the British Army during the War of 1812. The system of Court Martials within the British Army was set out in the Articles of War. There were four degrees of Court Martials (as laid out in the Standing Orders and Regulations for the 85th Light Infantry, London, 1813. Pages 135 – 139) By Tom Fournier

A visit to Fort George National Historic Site in Niagara-On-The-Lake, Ontario, Canada is sure to include the Officers’ quarters. Displayed on the wall in the dining room is a plaque detailing the Mess Rules for the 41st Regiment. They can also be found in the history section of our website here. The reading of the rules is fascinating. There certainly seems to be a preoccupation with a proper accounting of the wine consumed and the management of fines (to be paid in bottles of wine). I find it strange that there are no strictures about discussions surrounding politics and religion. It is also disappointing that there no limitations on feats of daring or animals brought into the mess (although maybe for the amusement of those in the mess perhaps it is not disappointing?) It is nice to see that the management of Betts (sic) are covered. What I find more interesting is the background as to why these rules were available to researchers so that they could be posted in the recreated dining room at Fort George. These mess rules are in fact found in the archives of the United States of America in a Department of State file for Miscellaneous Intercepted Correspondence 1789 – 1814, British Military Correspondence, “War of 1812 Papers”. By Tom Fournier

It is in June and July of 1804. The 41st Regiment of Foot have already been in Canada since the autumn of 1799. On behalf of the Board of Ordnance, Lieutenant Colonel George Glasgow of the Royal Artillery has supervised an inspection of the muskets of the 41st Regiment. He finds they are in a remarkably deplorable state. For those who love the minutia of detail associated with the British Army of the Napoleonic Age, his reports and summaries offer incredible and fascinating details! He wraps it all up with what I think is a shocking recommendation. Report – 20 June 1804 In the examination of arms belonging to the 41st Regt. Of Foot the following points have been attended to – Viz By Tom Fournier

In this blog post we look at new content posted in the history section of the 41st Regiment of Foot MLHG’s webpage. This is the remarkable (to me) Court Martial of Lieutenant Benoit Bender of the 41st Regiment of Foot, held in Montreal in July of 1815. http://www.fortyfirst.org/transcript-15-courtmarshall-benoit-bender.html The Court Martial occurred at the request of Lieutenant Bender after he was barred from further association with the mess of the Officers of the 41st Regiment in May of 1815 after Captain Peter Latouche Chambers made an accusation of cowardice against Bender. Chambers made this claim one evening, just after Bender excused himself from the mess. Bender asked for exoneration through a Court Martial but was told that he could not be accommodated right away. Finally, with a wide gathering of the Officers of the 41st Regiment and many others in Montreal for the Court Martial of Major General Henry Proctor (also the former commanding Officer of the 41st Regiment), an opportunity arose for the Court Martial of Benoit Bender. At the Court Martial he was arraigned on the charges but had to wait until November 27th, 1815 for this to be approved by the Prince Regent and posted by Horse-Guards. |

AuthorsThese articles are written and compiled by members of the 41st Regiment Living History Group. Archives

January 2023

Categories |