|

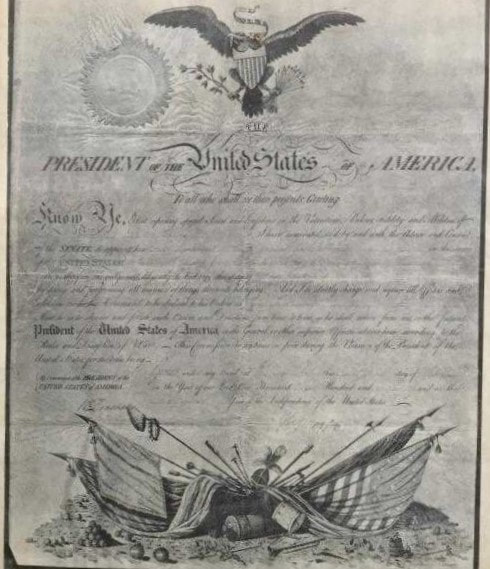

By Tom Fournier Whenever I hear the adage “if he did not have bad luck, he would have no luck at all”, I think of Porter Hanks. Lieutenant Porter Hanks is most often known as the American Officer who surrendered Fort Mackinac to an attacking British force representing one of the first land actions associated with the War of 1812. Porter Hanks was born in Massachusetts in 1785 (date unknown)[1]. He was appointed to be a 2nd Lieutenant in the Regiment of Artillerists on January 17th, 1805.[2] He was transferred that same month to serve in the frontier town of Detroit in the Michigan Territory. He was promoted to 1st Lieutenant on December 31, 1806 in the Regiment of Artillerists.[3]

Life in Detroit was not with out some benefits as it was in Detroit on January 7, 1807 that Porter Hanks married Margaret Jane McNiff, daughter of Patrick McNiff. Patrick McNiff was a loyalist who had fled to Canada during the American Revolution. He did work as a surveyor in Upper Canada but was passed over for the role of Deputy Surveyor General for Upper Canada. When the British withdrew from Detroit in 1796 due to the Jay Treaty, McNiff remained and was named surveyor for Wayne County.[4] Porter Hanks seemed to have a number of unfortunate interactions with the British Army. The first of which occurred in November of 1805. British Officers had arrived at Fort Detroit and announced that they were searching for a deserter from the 41st Regiment. The British Officers (Captain Adam Muir and Ensign John Stow Lundie of the 41st Regiment) spent the afternoon in the American Officers’ mess enjoying the hospitality and refreshments. An American Officer had reconnoitred the town and determined the location of the deserter. That evening, anticipating an entertaining adventure, a number of the American Officers accompanied the British Officers in their quest to apprehend the deserter. Unfortunately, the local citizens were offended at the thought of this poor deserter’s liberties being violated in their community and helped him resist arrest. A scuffle broke out which resulted in Muir discharging his pistol and having its ball pierce his calf. The British Officers were arrested and had to appear in court under their own recognizance nearly a year later in September of 1806. At the trial, the sentences resulted in massive fines to the Officers involved. Lundie’s was so huge that he faced a life in prison until it could be paid. After many protests by the British commander at Fort Malden and local American citizens, the sentences were reviewed and essentially struck. Amongst the American Officers involved were Abraham Fuller Hull (son of General and Michigan Territory Governor William Hull), Lieutenant Henry Breevort and of course Lieutenant Porter Hanks! A much more detailed account of this incident can be found at: 41st Blog.[5] Let’s move forward to July of 1812 where Lieutenant Porter Hanks found himself as commander of the American garrison of Fort Mackinac (known as Fort Michilimackinac to the British). This fort was taken over by the Americans from the British in 1796 due to the Jay Treaty. Its strategic position controlled access to Lake Michigan and had significant influence over the fur trade.[6] The British had set up a new post on St. Joseph’s Island to the north of Mackinac. Hanks had heard rumours of movements of indigenous peoples around St. Joseph’s Island and on the 16th of July he arranged with Captain Michael Dousman, a Mackinac resident and militia officer, to try to watch the movements around St. Joseph’s Island. Dousman started out by water and soon ran into and was captured by the attacking force.[7] This force under Captain Charles Roberts, consisted of 46 officers and men of the 10th Royal Veteran Battalion, 3 men from the Royal Regiment of Artillery, approximately 200 fur traders and 400 indigenous warriors.[8] Dousman was paroled with the promise that he would gather the citizens of Mackinac Island and put them under the protection of the British guard. The British had taken possession of an elevated position above Fort Mackinac. Seeing the British force was the very first indication for Hanks that a state of war had commenced. Realizing that his position was untenable, Hanks negotiated for honorable terms of capitulation. Hanks and his men marched out of the fort with the honours of war and were paroled. Lieutenant Hanks and his officers reached Detroit on the 29th of July, 1812.[9] This was a busy time in the area around Detroit. General and Governor of the Michigan Territory, William Hull had troops on the Canadian side of the Detroit River. He also had challenges preserving and protecting his supply lines from Ohio. On August 5th, indigenous warriors under Tecumseh ambushed a supply train near Brownstown. On August 9th, a large American force of 600 men were sent out from Detroit to find and escort an expected supply train moving up from the River Raisin. It was ambushed by a British and indigenous force led by Captain Adam Muir of the 41st Regiment (that same Adam Muir from the 1805 deserter affair). The Americans were able to drive off the ambush but not before sustaining significant losses (18 killed and 64 wounded). On August 11th, Hull pulled all of his troops back to Detroit. [10] In this tense environment, Porter Hanks was wanting to clear his name and preserve his honour. On August 4th he wrote a formal letter to Hull describing the situation he faced at Fort Mackinac, the consultations with his officers and local gentlemen and the mutual decision to surrender. He provided copies of the formal communications between himself and Captain Charles Roberts of the British. He closed his letter with the request, “I beg leave, Sir, to demand that a Court of Enquiry may be ordered to investigate all the facts connected with it, and I do further request that the Court may be specially directed to express their opinion on the merits of the case.”[11] General Orders were issued on August 14, 1812 for a Court of Enquiry on the Conduct of Porter Hanks to assemble on August 15th. Lieutenant Colonel Miller was appointed President, Captains Dyson and Baker were members and Lieutenant Bacon was to be recorder.[12] Early in the enquiry, it seems the documents presented by Hanks were entered into the court records. Of particular interest were claims by the British officer Roberts that a number of men in Hanks’ garrison were British subjects and some in fact were deserters from the British Army. Hanks seemed quite vehement in his defense of these men stating, “It is my duty, Sir, to observe that I know of no men of my former garrison to be British Subjects and must therefore, on behalf on my Government, claim them all as American Soldiers, and request that they be embarked as such.”[13] Hanks must have been successful as there is no indication of complaints by the American government like there was with captives from Queenston Heights who were held as deserters. It is at this point in time that local events and fate undermined Hanks attempt for exoneration. On August 15th, Major General Brock sent an emissary to General Hull demanding the surrender of Detroit. The request for surrender was refused and a bombardment commenced from a battery in Sandwich, Upper Canada and the British Provincial Marine vessels Queen Charlotte and General Hunter. The next morning, Brock crossed the Detroit River with 330 regulars (primarily 41st Regiment) and 400 militia (a number of whom wore cast off coats from the regulars) to join the 600 indigenous warriors that had crossed with Tecumseh the day before.[14] On the morning of August 16th, firing on Detroit resumed with a shot killing 5 men in the fort. General Hull immediately lost his nerve, sending out his Aide-de-Camp and son, Captain Abraham Fuller Hull (another of the actors from the 1805 deserter incident) with a flag of truce, indicating his willingness to surrender. Amongst the dead was Porter Hanks, with no further opportunity for redemption. [1] Robert Malcomson, The A to Z of the War of 1812, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., Lanham, Toronto, Plymouth, U.K. 2009. P. 234 [2] Colonel William H. Powell, List of Officers of the United States from 1799 to 1900 - Embracing a Register of all Appointments by the President of the United States in the Volunteer Service during the Civil War, and of Volunteer Officers in the Service of the United States. June 1, 1900 . June 1, 1900. L.R. Hamersly & Co., New York, 1900. Pg. 43 [3] Colonel William H. Powell, List of Officers of the United States from 1799 to 1900 - Embracing a Register of all Appointments by the President of the United States in the Volunteer Service during the Civil War, and of Volunteer Officers in the Service of the United States. June 1, 1900. L.R. Hamersly & Co., New York, 1900. Pg. 45. [4] Ron Edwards, “McNIFF, PATRICK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed May 6, 2019, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcniff_patrick_5E.html. [5] Silas Farmer, The History of Detroit and Michigan or the Metropolis Illustrated, A Chronological Cyclopaedia of the Past and Present, Including a Full Record of Territorial Days in Michigan and the Annals of Wayne County. Detroit, Silas Farmer & Co., Corner of Monroe Avenue and Farmer Street, 1889 [6] Robert Malcomson, The A to Z of the War of 1812, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., Lanham, Toronto, Plymouth, U.K. 2009. Pp 306, 337 [7] Jonathan Robertson, Adjutant General, Michigan in the War, W.S. George & Co., State Printers and Binders, Lansing, 1882. P. 1010 [8] Robert Malcomson, The A to Z of the War of 1812, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., Lanham, Toronto, Plymouth, U.K. 2009. P. 337 [9] Jonathan Robertson, Adjutant General, Michigan in the War, W.S. George & Co., State Printers and Binders, Lansing, 1882. P. 1010 [10] J. Mackay Hitsman, The Incredible War of 1812, A Military History. Robin Bass Studio, Toronto, 2000. Pp. 75-78 [11] Michigan Historical Collections, Documents Relating to Detroit and Vicinity, 1805-1813, Volume 40. Michigan Historical Commission, Lansing, 1929. pp. 432-433 [12] Michigan Historical Collections, Documents Relating to Detroit and Vicinity, 1805-1813, Volume 40. Michigan Historical Commission, Lansing, 1929. pp. 439 - 440 [13] Michigan Historical Collections, Documents Relating to Detroit and Vicinity, 1805-1813, Volume 40. Michigan Historical Commission, Lansing, 1929. pp. 446-447 [14] J. Mackay Hitsman, The Incredible War of 1812, A Military History. Robin Bass Studio, Toronto, 2000. P. 143

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsThese articles are written and compiled by members of the 41st Regiment Living History Group. Archives

January 2023

Categories |